The principles of questionnaire documentation are as follows:

0. Docuentation must make sense.

Principle 0 must be maintained at all times. Note that this does not refer to correcting mistakes in the questionnaire in order for it to make sense, but choosing the best method in which the questionnaire is documented. Ensuring the documentation makes sense should be the basis for all decisions made based on the principles below.

1. Maintain and do not alter the semantic meaning of the questionnaire.

Principle 1 is the overall aim of CLOSER's metadata ingest project and therefore the most important. CLOSER's target is to generate metdata for CLOSER Discovery for every instrument used by eight individual longitudinal cohort studies. CLOSER Discovery is designed for examining the logical flow and semantic meaning of the instruments. Therefore Principle 1 has to be kept to at all times.

CLOSER also intends that the metadata documented is capable of being shared with other Data Documentation Initiative (DDI) compliant organisations, hence Principle 1 also ensures that CLOSER produces consistent and comparable metadata.

The practice of keeping to principle requires decisions to be made as to what questionnaire elements provide meaning. For example it was decided that bold font provided no semantic meaning and therefore CLOSER is not documenting the weight of the font. The order of multiple choice options was deemed relevant and therefore special care is taken to preserve the order within the documentation.

The three following principles were conceived purposefully to give structure and guidance as to how the first principle should be followed at all times and in all situations.

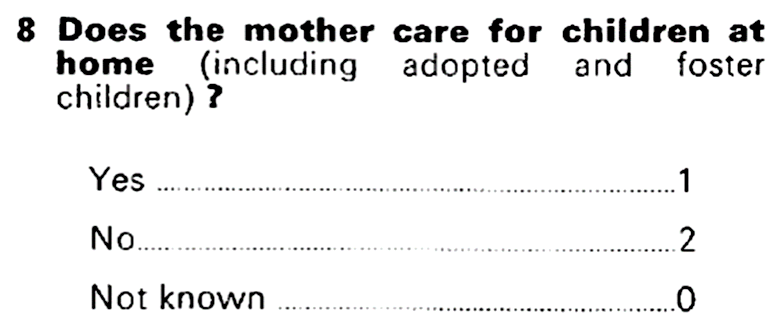

In example 1 below we can see that Does the mother care for children at home ... ? is in bold. We do not document this, however we do document that the order of the code list is Yes, No, No known.

Example 1 Birth Questionniare (BCS)

2. Do not correct the questionnaire.

Principle 2 is the second most significant principle for ingesting metadata. It is fairly common to find what seem like mistakes in the questionnaire design; these can range from typos (e.g. 'martial status' instead of 'marital status') to impossible condition logic (e.g. asking when someone gave up smoking, within a branch of non-smokers).

Any mistakes within the questionnaire could have altered the data being collected, and therefore it is important to avoid correcting the metadata while documenting. Also, what seems like a mistake always has the potential of being done purposefully and therefore potential mistakes should be verified.

In the case of a typo, the misspelt word can be aliased within CLOSER Discovery to allow effective searching (e.g. searches looking for the 'marital', would also find aliased questions with the word 'martial').

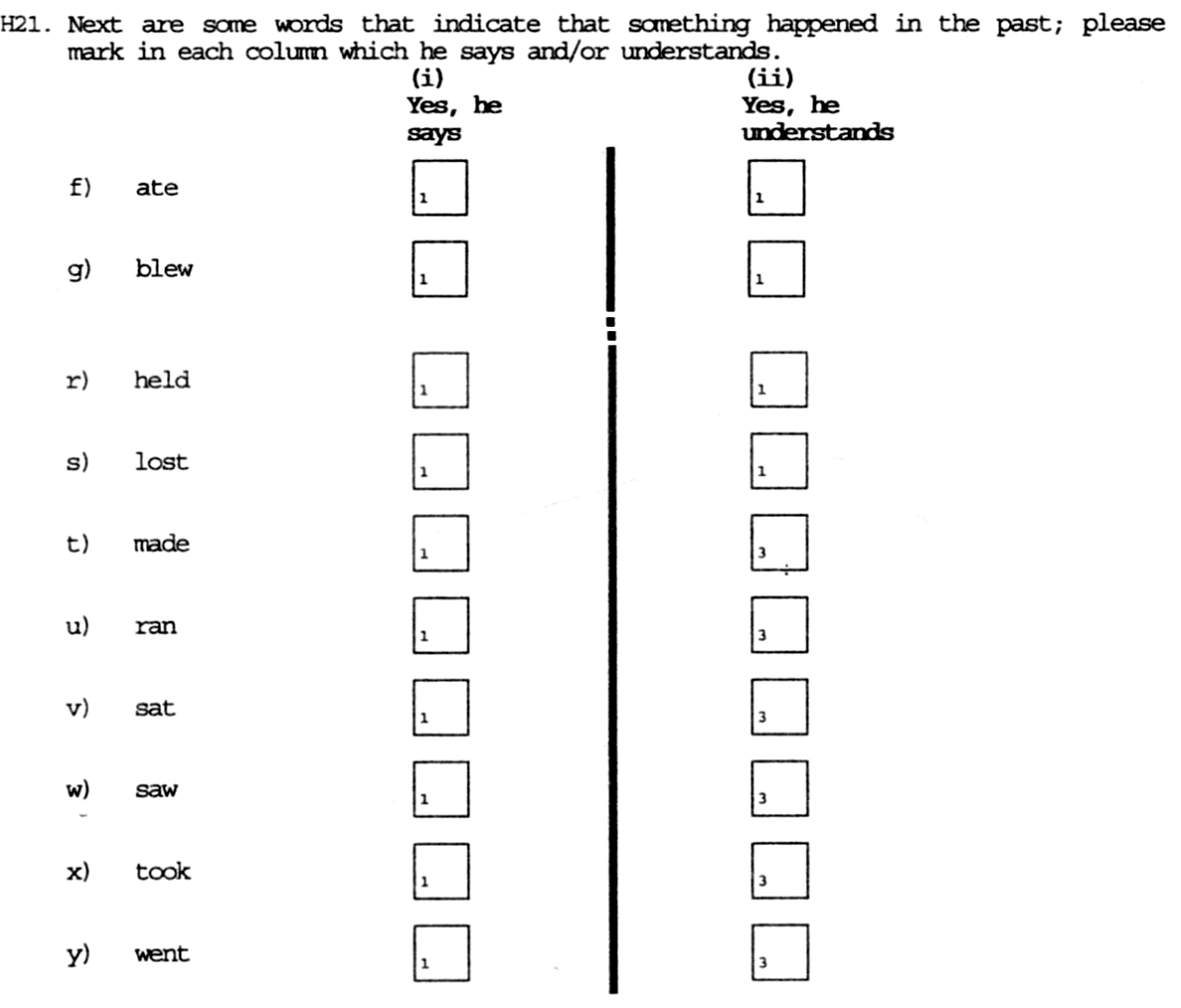

There are rare situations where Principle 2 must be violated in order to follow Principle 1 and document meaningful metadata. A real-world example of this is when a code value is accidently printed with the wrong value. There is no easy way to alias code values and CLOSER's documentation would suggest that there are two distinctly different codes, while the dataset would only refer to one of the codes. In this case, documenting the mistake would mislead the user and violate Principle 1.

Example 2 Questionniare My Little Boy/Girl (ALSPAC)

3. Only record what is contained within the questionnaire.

Principle 3 is the third most significant principle and therefore should be broken only when doing so maintains Principles 1 & 2.

It is important while recording historic metadata to refrain from adding additional information that is not within the questionnaire. A seemingly simple concept, but there are situations, particularly in older questionnaires, where the questionnaire does not provide all of the information to document meaningfully or to generate valid DDI. A real-world example of when not to add to the metadata is when a questionnaire asks

"how many?". 3.1

Often this question and similar questions can be found within a condition, immediately following a question similar to

"Do you own a car?". 3.2

Question 3.1 is largely meaningless without being able to see question 3.2, which makes it tempting to copy question 3.2's text and concatenate it with question 3.1 creating

"Do you own a car? how many?". 3.3

Doing this violates Principle 1, and is therefore forbidden. The solution to maintain context for question 3.1 can be found by accurate routing using conditional constructs. For example question 3.1's universe would contain "Answered yes to ‘Do you own a car?’".

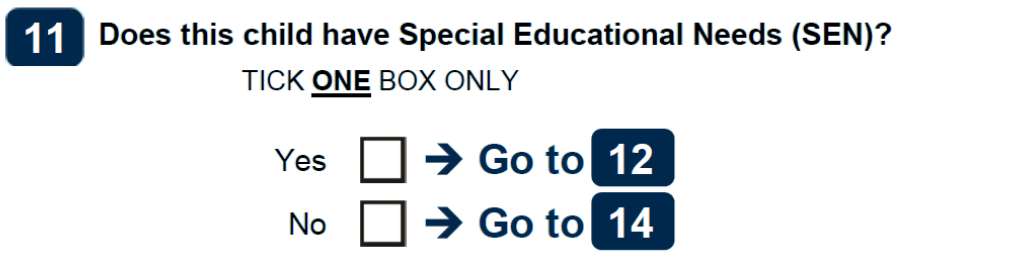

An example where the metadata must be added to in order to maintain Principle 1 is when a questionnaire uses an arrow to denote a condition. It is impossible to document an arrow literally and leaving it out of the documentation altogether changes the logical flow of the questionnaire. Therefore, text representing the arrow's meaning has to be added.

Example 3 Questionnaire Teacher Paper Questionnaire (MCS)

4. Do not allow the data recorded (i.e. the variables) to inform the metadata archiving.

Principle 4 is the final and least significant principle. Whilst documenting the structure, flow and intent of a questionnaire, it may seem harmless to consult the collected data in order to better understand the questionnaire being recorded. This practice, however, should also be avoided. The aim of the ingest programme is to record the instruments used for data collection as accurately as possible. Using information that was created after the collection event alters the perception and understanding of the instrument.

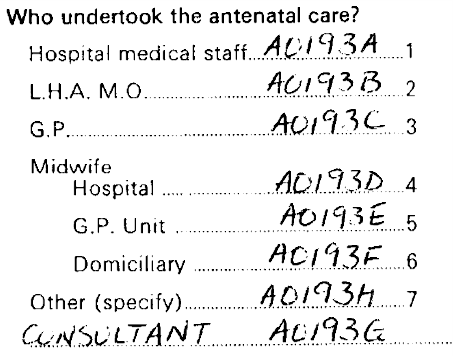

A very basic real-world example of this can be found when a question offers a set of multiple choice options and an "other (specify)" option. If the same response is often specified within the other option, then it is relatively common to code that answer in addition to the originally offered options. It is important not to document this additional coded answer, because it was not offered to the respondents and therefore potentially had an effect on the collected data.

The most common situation where breaking Principle 4 is valid is when Principles 2 or 3 must be broken. For example, in the situation where it is most appropriate to correct the questionnaire, it is obviously vital to check whether the mistake was intentional or not and if the mistake had a distinct effect on the collected data.

Example 4 Birth Questionnaire (BCS)

References

Poynter, W. and Spiegel, J. (2015) Protocol Development for Large-Scale Metadata Archiving using DDI-Lifecycle. IASSIST Quarterly, 39, 3, p.23-29.